Long, Short & Everything in Between

A Primer on Hedge Funds

Disclaimer: This article is only intended to provide you with general information. It is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any security and does not constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice. Any statement about a particular investment or company is not an endorsement or recommendation to buy or sell any such security. The article is not intended to provide legal, accounting, financial or tax advice, and should not be relied upon in that regard. You are encouraged to seek independent advice. Every effort has been made to ensure that the article is accurate as of the date of first publication; however, we cannot guarantee that it is accurate, complete, or current at all times. The article may contain forward-looking information that reflects our current expectations or forecasts of future events. Forward-looking information is inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties, and assumptions that could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed herein.

Hi friends, welcome to another week of ‘While You Wait’, a blog dedicated to alternative investments from a retail perspective. This week I’m writing about hedge funds. Most people have heard about hedge funds but few fully appreciate the impact they can have on investment portfolios. Rather than boring you with text book definitions and dense, jargon filled examples, I’ve summarized two well known hedge fund stories to shed light on the always evolving world of hedge fund investing. Let’s get into it!

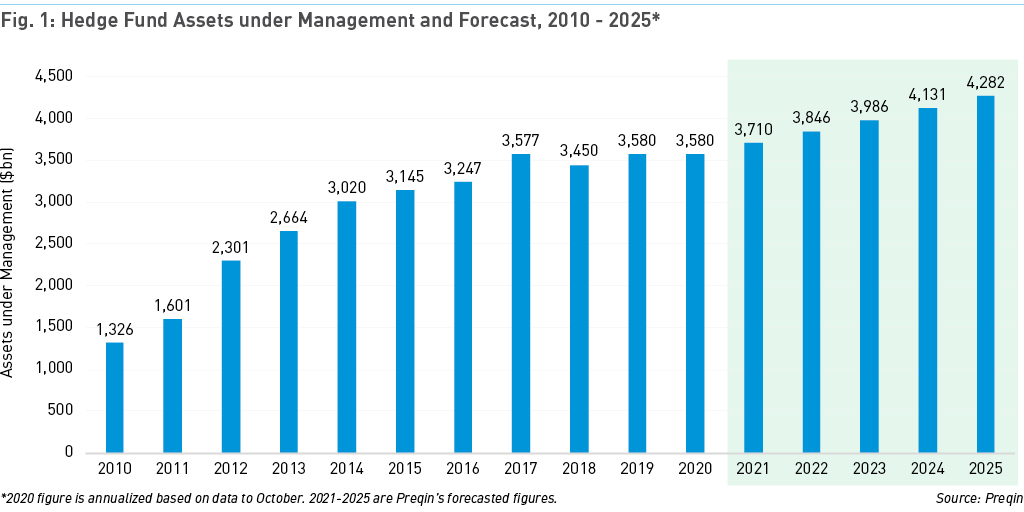

No asset class within investment management attracts more colorful characters or controversy than the hedge fund space. TV shows like HBO's, “Billions”, films like “The Big Short” and too many books to count all paint a picture of a world filled with egos and excess. The reality, in this instance, is actually stranger than fiction. The hedge fund world is filled with an eclectic mix of incredibly intelligent and driven individuals all looking for an edge to generate returns and manage risk for investors. What started in the late 1940s as a novel approach to investing in the stock market has since morphed into a $4+ trillion dollar global asset class comprised of a wide variety of investment strategies.

Sophisticated institutional and HNW investors have been relying on a variety of hedge fund strategies for many decades to generate uncorrelated returns, provide portfolio downside protection and solve for many other investment objectives.

So, what exactly are hedge funds?

According to alternative investments data company, Preqin, the term ‘hedge fund’ originally derives from the investment strategy of ‘hedging’ against market movements, maximizing returns and eliminating risks by choosing either long (buy) or short (sell) positions within the market – the aim being to profit regardless of market direction.

This definition most closely describes the investment approach of the first kind of hedge fund, which has come to be known as a ‘market neutral’ strategy. One in which the investment manager tries to eliminate market risk from the portfolio and focus specifically on the risks of the individual securities held in the portfolio (otherwise known as idiosyncratic risk). As an example, a manager might want to eliminate the risks associated with the S&P 500, while focusing specifically on the risks associated with Disney, Nike and Mastercard, three S&P 500 constituent companies. The manager would do this by buying Disney, Nike and Mastercard and selling an equal amount of the S&P 500.

Over the years, there has been an explosion in the variety of distinct investment strategies that, as a group, fall under the hedge fund umbrella. The common tools used by most hedge funds, irrespective of their specific investment strategies/approach include:

Leverage: The use of borrowed capital to attempt to enhance investment returns. The return to investors is equal to the return generated by the portfolio, plus the return generated through the use of leverage less any borrowing costs

Short selling: Selling borrowed securities today in the hopes that the securities will decrease in price in the future (i.e., sell high, buy low). The return to investors is equal to the difference between the price the securities were sold for and the price the securities were ultimately bought for (less any borrowing costs). As an example, say you sold a borrowed security for $10 today and bought it in one year at $5. During that time, you paid the lender $1 in interest. Your return would be $10 - 5 -1 = $4

Both leverage and short selling can also be achieved by using derivatives. For the sake of simplicity, we will leave derivatives for another day. In terms of performance, the last decade has been extremely challenging for hedge funds particularly relative to public equity markets, which have generated historically attractive returns. However, on a risk-adjusted basis, hedge funds have delivered value and I would speculate that hedge funds will perform substantially better going forward as volatility and uncertainty returns to public markets

Now that we have a foundational understanding of hedge funds, let’s turn to two well known hedge fund stories to highlight the kinds of strategies hedge funds use to generate returns. Readers should note that both stories highlighted are examples of rare and exceptional hedge fund successes, which should not be construed as representative of the typical experience investing in hedge funds. As always, do your own research.

The Quant

Recommended Reading: ‘The Man Who Solved The Market - How Jim Simons Launched The Quant Revolution’ by Gregory Zuckerman

The legend of the hedge fund firm, Renaissance Technologies or Rentec, is known by investment professionals around the world. The firm is credited with creating and popularizing the quantitative approach to investing. Rentech’s flagship hedge fund, the Medallion Fund, generated average annualized returns of 66% (39% net of fees) between 1988-2018, an average return that no other hedge fund or investor has ever come close to replicating. Unfortunately, the fund is closed to outside investors and only manages Rentec employee capital (a decision made some years ago).

The enigmatic founder behind Rentec, Jim Simons, was a mathematics prodigy who went on to study at MIT and UC Berkley before joining Harvard in the 1960s where he taught for a time. After Harvard, he joined a US intelligence agency tasked to crack Soviet codes during the cold war. There he honed his skills in using advanced mathematical models to identify patterns in seemingly meaningless data and developed an ultra-fast code-breaking algorithm before leaving (in the late 1970s) to ultimately launch one of the first quantitatively driven investment companies, Monemetrics.

At Monemetrics, and in collaboration with mathematicians and other academics brought onto the team (many of whom had achieved exceptional heights in academia), Jim Simons began gathering huge amounts of stock market, currency and commodities related data dating back to pre-World War II (this was likely amongst the most comprehensive effort to gather and analyze financial data ever undertaken and one of the most substantial investing edges held by Rentec). Using advanced mathematical techniques and models, the Monemetrics team began identifying patterns in financial data with the ultimate goal of being able to predict market moves. In order to realize the full power of their approach, Jim Simons and his team brought in substantial data storage and computational power, which they paired with direct access to real time market data, something no other investment firm had done before Rentec. Thus, Renaissance Technologies was born, the first investment firm to deeply leverage technology and advanced mathematics techniques to recognize patterns, generate signals and capture substantial investment returns over time.

Today, the field of quantitative hedge fund investing represents roughly 30+% of all global hedge fund assets under management as thousands of hedge fund managers look to utilize research from the worlds of physics, mathematics and other advanced sciences to identify and extract value from pattern recognition in markets.

The Cynic

Recommended Reading: ‘The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron’ by Bethany McLean, Peter Elkind

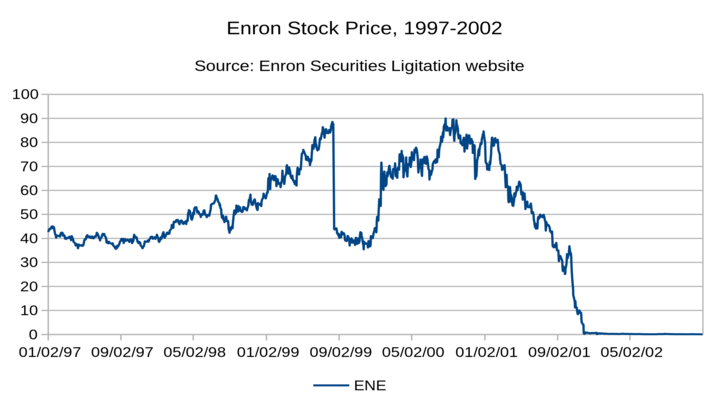

In November of 2000, Jim Chanos, founder and managing partner of Chanos & Company LP (formerly known as Kynikos Associates LP), a hedge fund specializing in short selling, initiated a short position on Enron, an American energy, commodities and services company. At the time Enron was one of the most successful publicly listed companies in the world with a market cap that exceeded $60 Billion, generating substantial profits for shareholders and receiving ample praise from sell side equity analysts as well as institutional investors. At the time the short position was initiated, Enron’s stock price sat at around $90/share with a consensus target price of $130/share. What followed was one of the most historic corporate collapses of all time. In a matter of months, Enron’s stock price dropped to zero as Jim Chanos and his firm generated a $500 Million profit on the trade.

Jim Chanos attended Yale where he studied economics and political science in the 1980s. After graduating, he broke into the investment industry as an analyst at brokerage firm, Gilford Securities, where he began honing his short selling skill set. While at Gilford, he put forward a sell recommendation on a company named Baldwin-United, which ultimately filed for bankruptcy in 1983. He then went on to work for Deutsche Bank as well as several other firms before hanging his own shingle in 1985 when he established Kynikos (Greek for ‘cynic’), an investment firm that focused on identifying short selling investment opportunities through deep fundamental stock research (think Warren Buffet but for short selling).

In late 2000, a friend told Jim Chanos about an article in the Texas Wall Street Journal that spoke to controversial accounting practices that the Securities & Exchange Commission (“SEC”) had recently approved for energy firms, including Enron. The approved accounting practices would allow energy firms to utilize ‘mark to market or market to model’ valuation practices, essentially allowing energy companies to massage their financials by adding in the current value of future expected profits. This was the initial sign of troubling financial reporting practices that piqued the interest of Jim Chanos and his team who then went on to deepen their research on Enron only to uncover further red flags including hidden financial losses, purposeful misleading of investors and regulators, and establishing shell entities to conduct ‘off-balance sheet’ transactions that often-involved Enron executives (significant conflict of interest). Furthering their belief that Enron was a bubble waiting to burst was company disclosure highlighting insider stock selling through the second half of 2000, a sign that not all was as it seemed. All of this intel combined was enough for Jim Chanos to begin shorting the Enron stock. As the company brought further bad news to light, Jim Chanos and his team increased their short position, which ultimately ended up being a prophetic move resulting in one of the largest profits from a single trade in history.

Today, short selling continues to be a core feature of hedge fund investment strategies, however, dedicated short sellers who fundamentally believe that the companies they short are deeply flawed, are far and few. The risks typically outweigh the rewards, even in cases when the short seller ends up being right! A recent example is the WallStreetBets subreddit VS. hedge fund, Melvin Capital.

Readers, if you’re enjoying my blog content so far, I encourage you to share it! Up next is my first post on digital assets or cryptocurrency investing. If you have any topics you’d like to see me cover, reach out with suggestions!